New book delves deeper into the mystery of the Lost Boys of Pickering

Published September 20, 2022 at 9:21 am

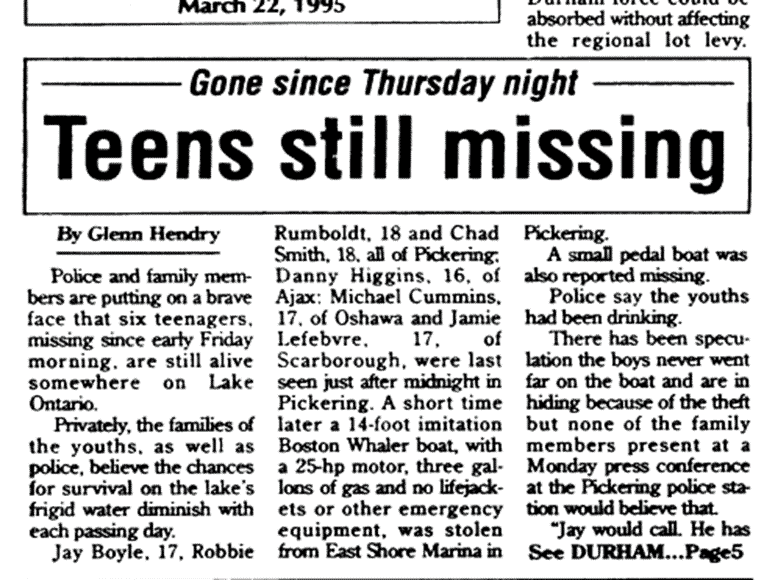

In the wee hours of St. Patrick’s Day, 1995, six local youths allegedly stole a boat from East Shore Marina in Pickering and went for a joy ride on the frigid waters of Lake Ontario, never to be seen again.

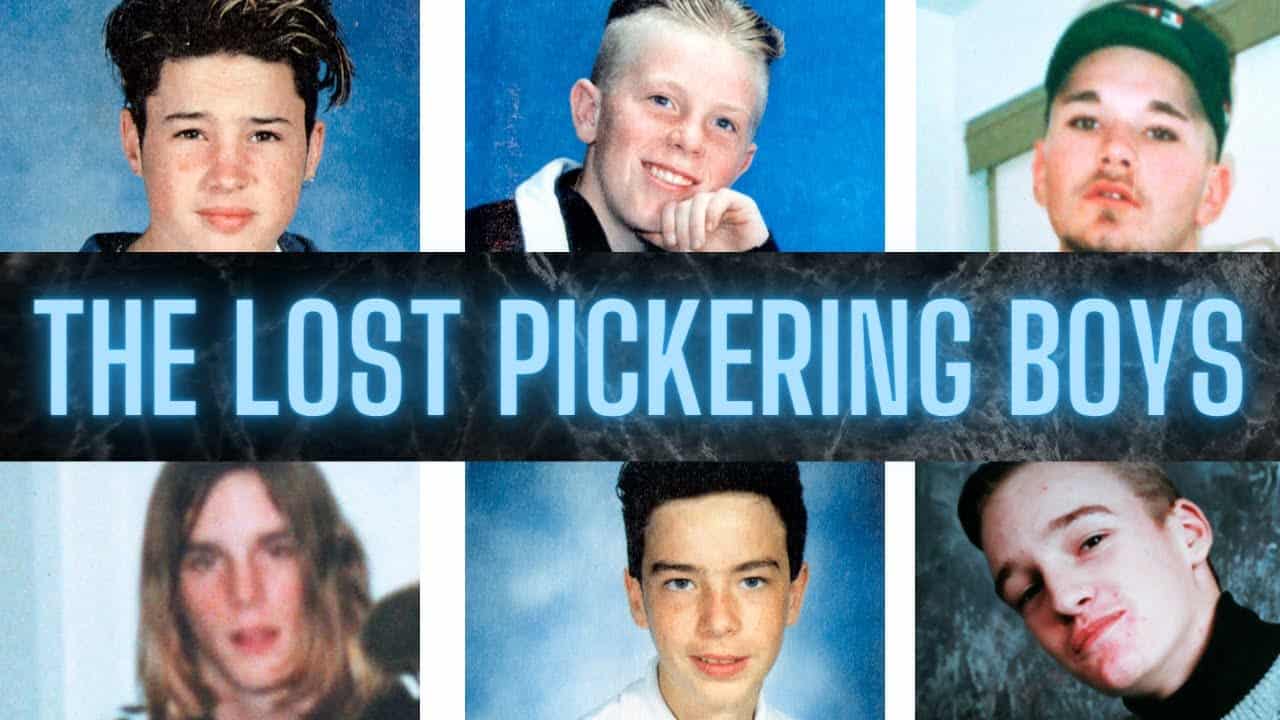

At least, that’s the view of Durham Regional Police, who believe that Jay Boyle, 17, Chad Smith, 18, and Robert Rumboldt, 17 all of Pickering; Danny Higgins, 16 of Ajax; Michael Cummins, 17 of Oshawa; and Jamie Lefebvre, 17 of Scarborough boarded a 14-foot Boston Whaler-type boat that night that subsequently capsized in Lake Ontario.

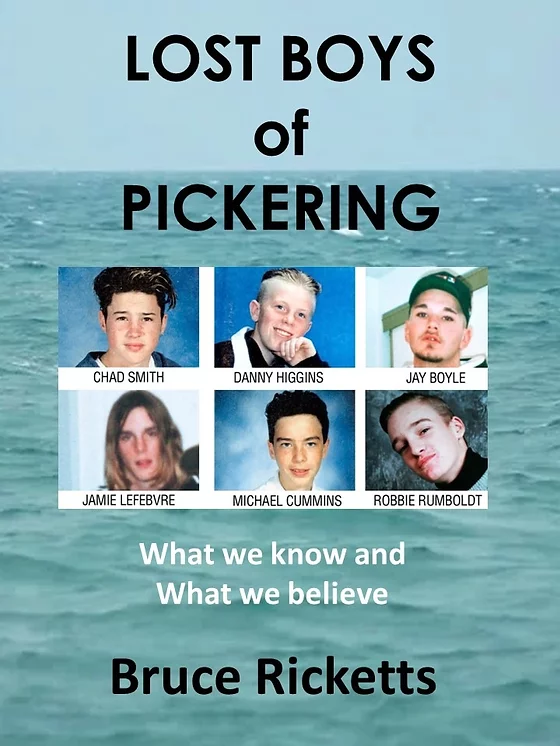

But an upcoming book on the subject by Ottawa-based author and private investigator Bruce Ricketts says there is “no concrete evidence” to support the theory. What’s more, Ricketts, who got involved in the case 12 years ago and has spent the last three years researching the story, believes Durham Police were slow to react to the disappearance of the six boys in 1995 and quick to jump to a conclusion and effectively close the investigation.

“At this time, based on limited and heavily redacted materials provided by Durham Police, we cannot conclude that the boys stole a boat or drowned in the lake. There is no concrete evidence to support that theory. The truth is that we do not know what happened or where. Nor do we know the fate of the boys.”

Rickett’s book, The Lost Boys – What we Know and What we Believe, is available on pre-sale now and will be released in November.

The spark that led to the book, Ricket explained, was a conversation he had with a friend in Ottawa in 2010. Ricketts runs a website called Mysteries of Canada, which delves into historical stories from conspiracy theories and maritime mysteries to urban legends and hidden treasures and his pal thought the Lost Boys would make a great research topic.

“When I started digging into it I realized that maybe the story wasn’t being told correctly. And it just ballooned from there.”

Besides the working police theory not based on any facts, Ricketts found out other information that made him suspect there was much more to the story, beginning with video from the marina that night.

Footage clearly shows three of the boys – Cummins, Lefebvre and Rumboldt – at the marina. But there were also other people – both before and after the appearance on the video by the youths – and vehicles, none of which showed up on DRPS reports or were investigated at all, Ricketts said.

Not to mention the fact that the first time Ricketts asked about the video he was told it did not exist. It was only after his third Access to Information and Privacy request (AITP) that he finally saw got to see the video, by this time heavily redacted.

Although reports at the time of the disappearance (The Bay News, March 22, 1995 – “Durham police to continue searching”) referenced a video tape of three of the youths entering the marina … the AITP response states, on Page 2, “With respect to the video portion of your request, be advised a thorough search of Durham Regional Police records produced negative results. Therefore we are advising you that with respect to this portion of your request, no records exist.”

That was the first example of stonewalling from local police forces on the investigation and it got his attention. “So I started asking questions,” Ricketts said. “From ’95 on Durham Police didn’t seem to give a shit.”

Ricketts said two of the girlfriends who were at a party with the boys earlier contacted police at 3:30 that morning. But their story seemed to be taken “very lightly” by DRPS Officer James Gillam, who was the first point of contact for the girls. Gillam told them to tell the mothers of the missing youths to file a report “now or in the a.m.” He also writes that he told the girls that since “no specific locations were known to look for the boys that I couldn’t do much for them,” adding that [name redacted] “was not truthful” and that “the boys were not in danger.”

Gillam’s report was not filed until March 23, almost a week after talking with the girls and was only written at the request of his superior.

It was Friday at 12:40 a.m. when the youths left the party and 3:30 a.m. when they were first reported missing, but it took until midday Saturday before police acted and even then, only by assuming that the youths were connected to the missing vessel, Ricketts claimed.

The official search began Saturday afternoon, where Durham Police were joined by the Metro Toronto Police marine unit, the Coast Guard and a C-130 aircraft and helicopter from the air-sea rescue unit at Canadian Forces Base Trenton.

They found nothing that the DRPS considered of value to the investigation. However, our analysis of some of the sightings reported by searchers should have, in my opinion, warranted further follow-up. Hundreds of volunteers from across southern Ontario joined the search, but no bodies, vessels or pieces of clothing, in the determination of DRPS, connected to the missing youths were found.

The fact that Durham Police apparently didn’t ask for assistance from other police forces after the initial search didn’t help the investigation either, Ricketts noted.

The OPP response was that no files exist with respect to this case. That is possible as we can find no reference to the OPP being asked to support this case. However, we find this rather puzzling, as a 25 mile radius (the maximum distance for travel ascribed to the Boston Whaler, given the gas volume estimated) from Pickering could have taken the boat outside of the jurisdiction of the DRPS.

The RCMP responded with the comment that they searched their records, and no files were found. This is odd, in that the potential search area crosses the international border. Again, we can find no record of DRPS requesting assistance from the RCMP.

Ricketts has filed nearly 30 AITP since he began his research into the story and it’s not just DRPS that has been stonewalling him in his investigations.

One particularly difficult request has been with the Toronto Police Marine Unit, he said.

On 1 May 2021, I requested, through ATIP, copies of communications between TPS and DRPS with respect to the 1995 case. The intent of the request was to fill in the gaps in the investigation by DRPS. The request was refused based on … Presumed Privacy.

I appealed the refusal to the Information and Privacy Commission (IPCO) who tried to mediate between me and TPS. The result was negative. However, on 25 January 2022, TPS issued an Amended Decision Letter which amended their first reply citing privacy and instead stated: “a thorough and complete search… failed to locate any records responsive to your request.” I immediately amended my complaint to IPCO to include the question of TPS’ honesty in processing my ATIP in that they first stated a privacy issue and then amended it to say there was no records found. Why the contradiction?

On April 10, 1998, a body of a man was recovered from the Niagara River, near the water intake channel for Sir Adam Beck Hydro Generating Station, by Niagara Regional Police. The description of the body roughly matched that of Jay Boyle, right down to the red Levis jeans found on the body.

The potential breakthrough should have returned the investigation into the disappearance of the Lost Boys to prominence, but instead the discovery was hidden, and it was 15 years later, in late 2013, when Boyle’s family learned of it.

They immediately requested Detective Sheridan of the DRPS to investigate this potential lead by requesting that a DNA profile be done by Niagara Police on the bone that was found in the jeans and compared to the DNA profile of Jay’s mother, a copy of which was on file at DRPS headquarters in Oshawa. According to Sheridan, in a communication with Amanda Boyle, Niagara Police refused to do the profile for two reasons: Cost was number one (even though the Boyle family said that they would cover it) and the second reason was based on a fact that a body drowned in Lake Ontario could not drift into the Niagara River due to the water currents.

This reason would have been valid, Ricketts believes, except for the fact that there was no concrete evidence to conclude that Jay Boyle was lost in the lake in the first place.

What followed was more stonewalling and more buck-passing, Ricketts claimed.

He sent an Access to Information request to the Niagara service, using case numbers supplied by the OPP, along the description of the case, date and location of the unidentified remains. Niagara Police told him it was “an OPP matter” and his request was denied.

He then contacted the OPP Missing Persons unit and was told that the OPP case number was merely an identifier for their database and that the case was indeed owned by Niagara Police. The contact also provided the NRPS case number which was used to refile the AITP in early 2014.

This second request was also refused because, as was declared by a Freedom of Information officer on January 29, 2014, it was not accompanied by a notarized ID.

“There is no requirement in the Municipal Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act of the province of Ontario to provide notarized ID when requesting ATI files,” Ricketts said. “It was my opinion that NRPS’ two refusals were a form of obstructionism.”

It took a third ATIP before Ricketts finally received a copy of the report, now heavily redacted.

After another delay (because the box containing the bone was “misplaced” during a renovation) Niagara Police finally agreed to send the bone to the Ontario Coroner’s Office for DNA analysis.

After all that the Ontario Coroner declared a “negative outcome” but Ricketts questions the validity of that conclusion because of the long delay in sending the evidence and because in a memo between the Niagara Police and Ricketts, he was told the evidence box was in the care of the Hamilton Hospital’s pathology department since the bone’s discovery in 1998.

“But in a conversation with the Chief Pathologist at the hospital, it was stated that no items such as this would be kept for 16 years and that there was no secured lock space at the hospital to store evidence. This contradiction tells me that the Chain of Evidence for the pants and bone was broken and casts further black clouds over the veracity of the findings by the Ontario Coroner.”

There are many other discrepancies in the investigation that has Ricketts questioning the findings of police, particularly in Durham, where there is testimony to suggest that the police had bad relations with one of more of the boys and that relationship may have tainted their view of the case.

The entrance to Lake Ontario from Frenchman’s Bay in Pickering

“DRPS had many encounters with this group of youths and as a result, it is suggested that their shoddy approach to this case was based on “payback,” Ricketts suggested.

Durham Police also had an opportunity to use sidescan sonar technology – used to search for Avro Arrow rocket models in Lake Ontario and shipwrecks off Cuba and Mexico and many others – to search the lake for any evidence of the boys and the boat. DRPS did contact Ed Burtt, the founder of Ocean Scan Systems in Belleville but before he could mount the search, DRPS cancelled the contract and a lake bottom search using sidescan sonar was never performed.

There was also the discovery of red gas can with bilingual markings discovered almost two weeks following the disappearance of the boys.

A U.S. Coast Guard Boatswain (DRPS Report #163) spotted and retrieved a “24 litre orange Yamaha gas tank” along the shore of Lake Ontario near Wilson, New York. The tank was found inverted and without a cap. The tank was brought back to Canada and identified by a marina staffer in Pickering as from the missing Boston Whaler.

But if the gas can had no cap and it floated for nearly two weeks in the rough waters of late March Lake Ontario, Ricketts asked, wouldn’t it have flipped (probably many times) and eventually filled with water and sank?

There’s also the matter of Danny Higgins. The youngest member of the group had an argument with Boyle at the party the night of the disappearance and left. There is no evidence that he met up with them again that night and it has been stated, by persons close to the young man, that Higgins was not a member of the group of friends when they disappeared.

There were also numerous sightings of some of the boys in the days that followed their disappearance, but they either weren’t followed up on or were never taken seriously.

As far as Durham Police is concerned, the case remains unsolved, and the boys are still considered missing. Anyone with any information that might assist investigators is asked to contact the DRPS at 1-888-579-1520, ext. 2511.

Meanwhile, Ricketts said on a Facebook page dedicated to the mystery of the Lost Boys of Pickering that he and the Boyle family have requested the Ontario government to direct the OPP to open a new case to re-investigate the 1995 loss and the 1998 bone recovery.

“We will keep this Facebook Page apprised of any significant developments as we move forward, but we ask friends and family of this case not to charge off contacting police or politicians demanding action. There is a process for all of this and the process has begun. It has been 19 years since the loss of the six boys. If it takes more time to get a resolution then so be it, but there will be answers to our questions.”

Ricketts has written two books prior to this one. His first book, based on his www.mysteriesofcanada.com web site and entitled, The S.S. Ethie and the Hero Dog, took five years to investigate and was published in June 2005. In his latest non-fiction work, The Provinces Must Go, he describes how Canada came into being and the structure of government designed by the Fathers of Confederation.

For information on The Lost Boys – What we Know and what we Believe, go to https://www.facebook.com/lostboys95

INdurham's Editorial Standards and Policies